In a recent Preferred Shares podcast, Andvari’s Chief Investment Officer and his two co-hosts continued with their series on the various industries benefiting from the construction (and continual maintenance) of the interstate highway system of the United States. In particular, the podcast focused on the early history of Vulcan Materials (VMC) and the handful of reasons of why these types of businesses are so great.

BIRMINGHAM SLAG HISTORY

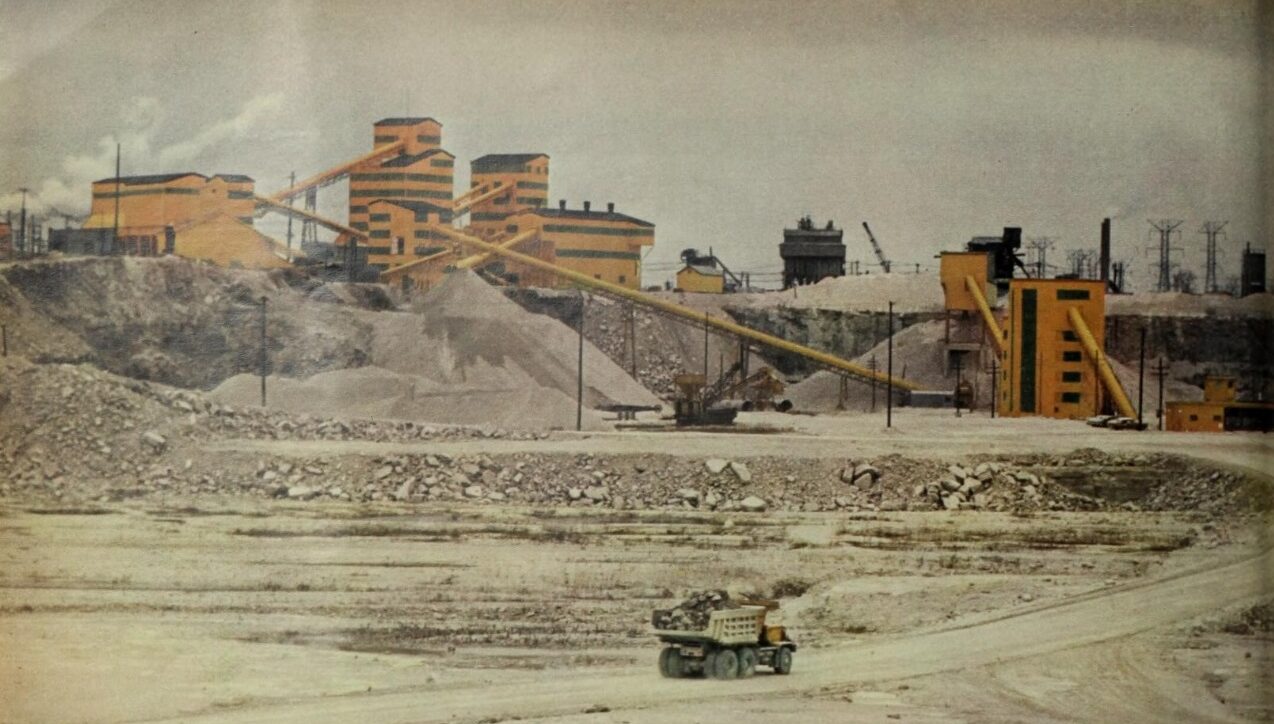

The story of Vulcan begins with Birmingham Slag, a business founded in 1909 by Solon Jacobs. The purpose of the new venture was to repurpose the remnants of the steel making process for use in road construction and as ballast for railroad tracks. After years of successful operation, Jacobs sold the business in 1916 to the Ireland family.

With extreme frugality, the Irelands successfully grew the business. They opened new plants and acquired several sand and gravel pits in the southeast. With this growth, Birmingham Slag would eventually win bids on significant projects. They provided materials and services for the Tennessee Valley Authority and the Manhattan Project.

After World War II, Birmingham Slag and many other family-owned aggregates businesses had the enormous opportunity afforded them by the passage of the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956. However, Birmingham Slag and its competitors all lacked the scale and capital to fully take advantage of this opportunity.

For Birmingham Slag, the solution was to acquire a public company called Vulcan Detinning in 1956. With this acquisition, Birmingham Slag became a public company (renamed Vulcan Materials) and could more easily raise capital. It also now had a currency with which it could acquire other aggregates businesses. For the other small players in the industry, selling to Vulcan was an attractive proposition as many were facing significant estate tax issues. They could sell to Vulcan not for cash, but in exchange for Vulcan shares, which eased their tax issues.

In four short years, Birmingham Slag transformed into Vulcan Materials, the nation’s largest producer of aggregates. Annual revenues went from $21.4 million in 1956 to $110 million in 1959 as they acquired numerous family-owned quarries.

INDUSTRY DYNAMICS

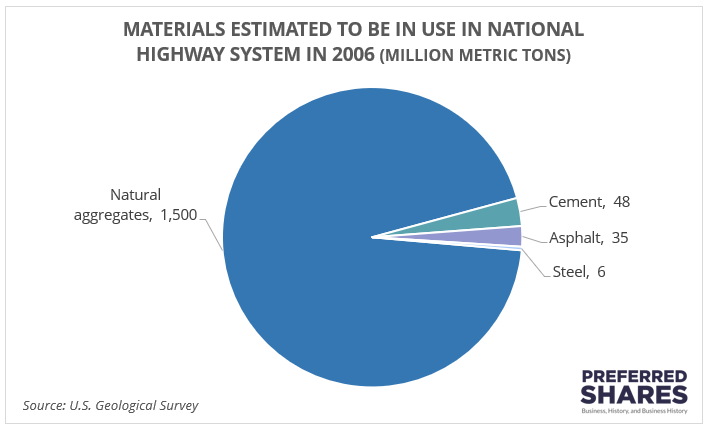

One great quality about the aggregates business is that there is no alternative to crushed rock for infrastructure and construction projects. For example, in 2006, the U.S. Geological Survey estimated that there was 1.5 billion metric tons of natural aggregates in use in the national highway system while there was just a combined 89 million metric tons of cement, asphalt and steel. Natural aggregates accounted for 94% of these total materials.

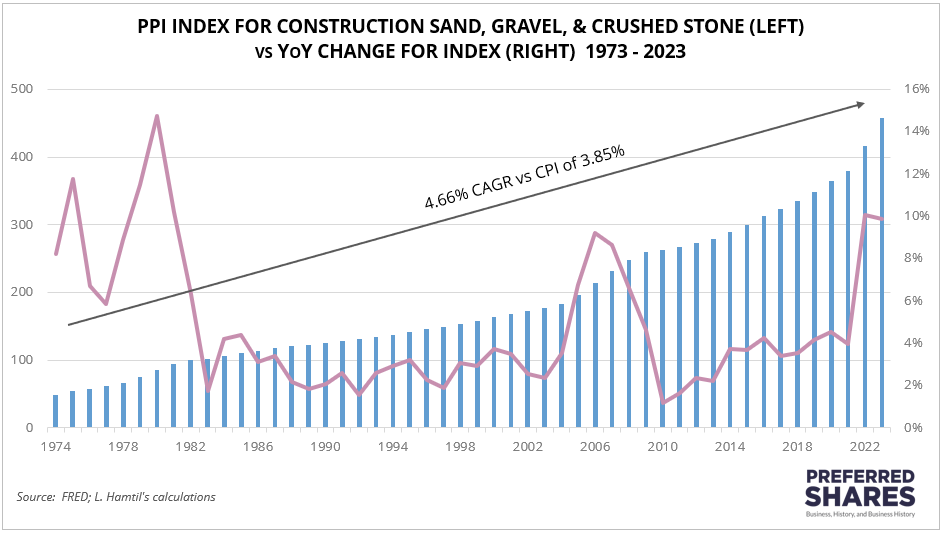

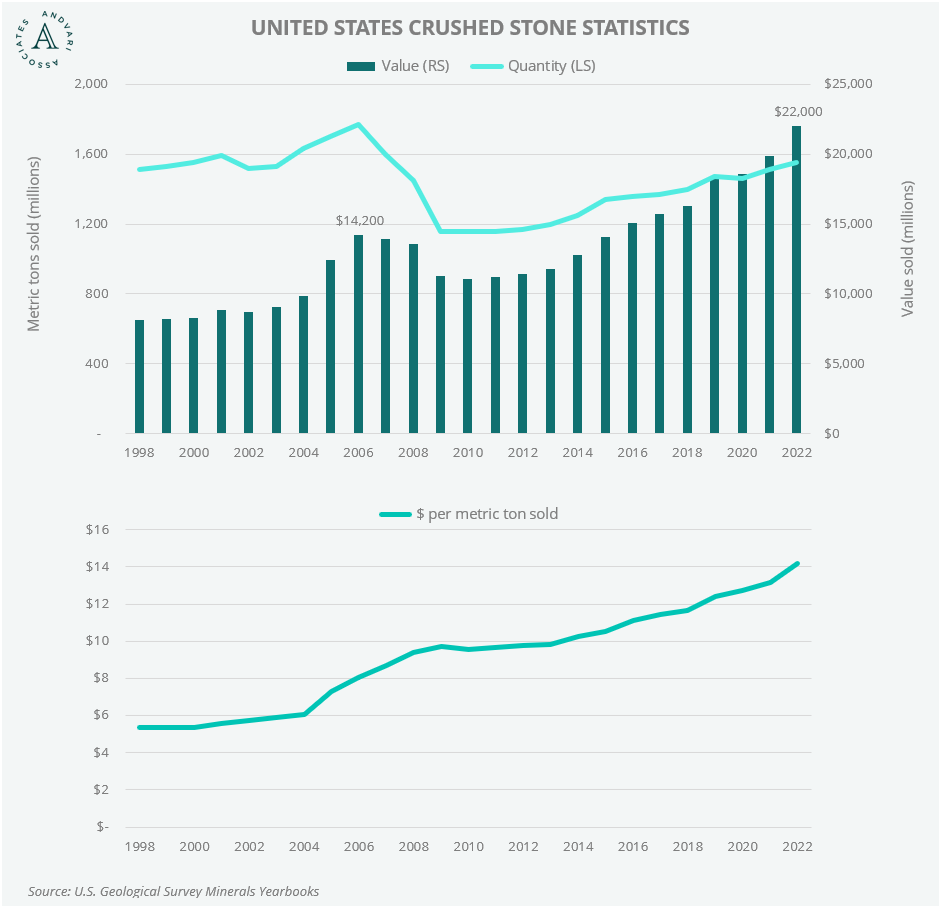

Another excellent quality of an aggregates business is its pricing power. The average price of a metric ton of crushed stone in the U.S. was $14 in 2022. However, transportation costs can quickly evaporate that purchase price based on travel distance. Thus, aggregates must be sourced locally, which gives these businesses the power to raise prices slowly and steadily above the rate of inflation. See Lawrence Hamtil's blog post “Rock Pile Riches”.

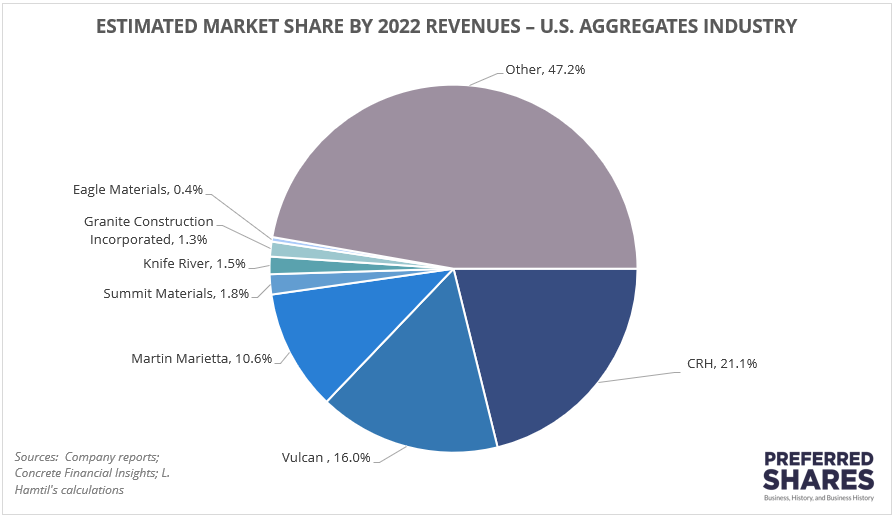

Despite several generations of consolidation, the industry remains highly fragmented. Further, the opening of new quarries is close to impossible given the permitting and regulatory hurdles. Thus, there is ample opportunity for the larger players like Vulcan, Martin Marietta, and others, to continue to consolidate by acquiring the large number of smaller players.

ANDVARI TAKEAWAY

The aggregates industry is one that will persist for many generations going forward. It exhibits many of the attributes that Andvari values. There is reliable and predictable growth from the continual spending on vital infrastructure maintenance and new construction projects. The industry has pricing power and there remains an opportunity for the large public companies to consolidate what is still a highly fragmented industry.