The study of history is an important part of the investment process at Andvari. For any company that interests us, we analyze the industry in which it participates. This helps us appreciate the evolution of technologies and organizations. We learn how the needs of customers have evolved. We can understand what motivates leaders and how they might react to changing environments. Most importantly, this information positions Andvari to better estimate the prospects of a potential investment.

The article which follows is a brief summary of a deep dive we recently initiated into the history of the desktop publishing software market from its founding in 1984 until the 2000s. These are the software programs used to edit graphics and to lay out pages for documents ranging from brochures to newsletters to magazines. Our longer paper focuses on the unique histories of each of the space's three, major players: Aldus, Adobe, and Quark.

Our complete, 18-page PDF on the space is available upon request or via Andvari's Client & Prospect Client Document Portal. Please contact Info@AndvariAssociates.com to inquire about access.

7 Key Takeaways from 35 Years of DTP Software

The desktop publishing (DTP) market was created in 1985 by Paul Brainerd who founded Aldus Corporation. Brainerd studied business and journalism in school and worked as an assistant to the operations director at the Minneapolis Star. It was there Brainerd learned to use a terminal-based editing and layout system made by Atex. Customers of Atex included some of the largest publishers in the world: The New York Times, Boston Globe, Chicago Daily, etc.

The unique history of the publishing niche within the more broadly explosive software industry is a worthwhile study. In fact, it is a representative example of many core values and concepts we embrace at Andvari with which we seek long-term investments. We work through the enduring lessons highlighted below, which are still applicable to investing today and to all businesses. But we certainly encourage our readers to 'go deeper' via our PDF if they are so inclined.

#1: Valuation Multiples Can Compress Quickly

The hot stock of today can eventually disappoint shareholders by failing to live up to unrealistic expectations. Aldus was one such example even though it was pivotal in the creation of an entirely new market.

Microstrategy is another example. The company made business intelligence software, was growing quickly, and IPO’ed in 1998. Shareholders who bought at the IPO and held until 12/4/2020 have underperformed the S&P 500 by 200%. A recent example might well turn out to be Zoom Video Communications. Zoom IPO’ed in April 2019, revenues have been tripling year over year, shares are up more than 500% since the IPO, and it trades at 60x trailing twelve month revenues. Many things must fall into place for Zoom shareholders to earn a decent return going forward.

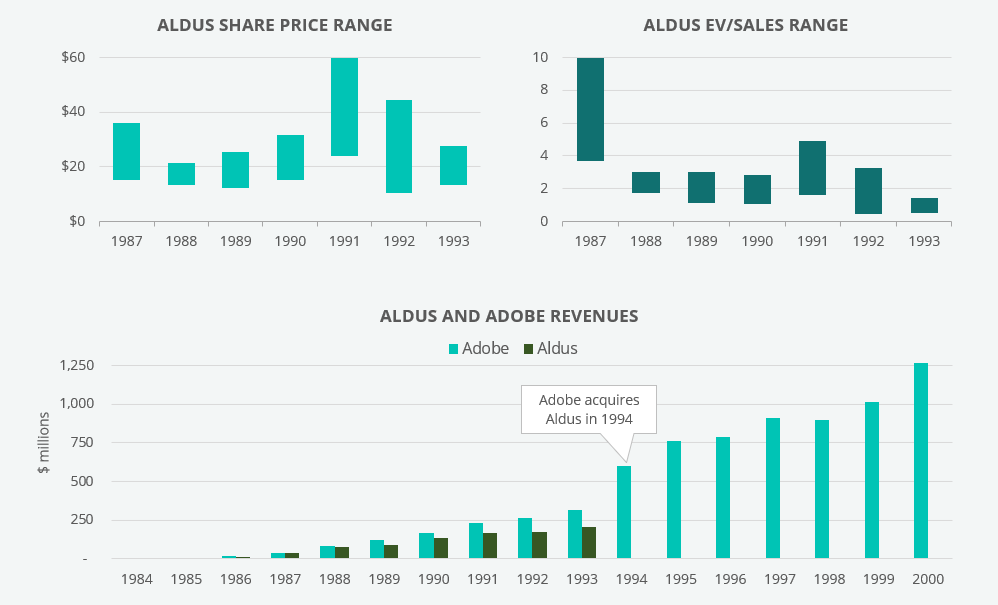

At its highest price in 1987, Aldus traded at a 10x enterprise value to sales ratio (amusingly quaint by today’s high growth standards). Revenues were $39 million in 1987 and went to over $200 million in 1993. The lowest EV/sales ratio was 0.45x, just five years later. It was a highly competitive industry and Aldus did not have as broad and deep of a product offering as Adobe. Furthermore, Aldus’ founder and CEO had simply ran out of steam. Adobe acquired Aldus for a price in 1994 not much higher than when Aldus came public.

#2: Know Your Customers and Take Care of Them

A business should always know who their customers are and do their best to take care of them. We see this at play from the very beginning of Aldus. Founder Brainerd initially thought the target market for Aldus’s publishing software would be small newspapers who would appreciate the time and money savings. If he had chosen to never interview these potential customers, he would have built a great product and then waited a year or two before making a sale. Instead, by taking time to learn about one set of potential customers, Aldus shifted its focus to a set of customers that could make decisions more quickly. In turn, these customers would see the benefits of PageMaker more quickly and help evangelize the product.

Although Quark was extremely successful in creating a product well-suited for the high-end of the publishing industry, its dominance of a market slowly eroded because of its arrogance and hubris. It simply no longer put customers first.

Quark would outsource all customer service to India. Customers would have to pay $15 per emailed support question. The CEO would publicly dismiss the concerns and desires of its customers. Quark chose not to reinvest in its business. Although it took over ten years, Quark eventually lost its dominant position.

#3: Better Together/Bundling

We see how partnerships can play out successfully with the example of Aldus, Adobe, and Apple. This partnership allowed for the creation of the desktop publishing market. Aldus had the software, Adobe had the underlying technology, and Apple had the hardware. With any one of these elements missing, it’s likely the creation of this new market would have been delayed. A combination of the right technologies can be extraordinarily powerful.

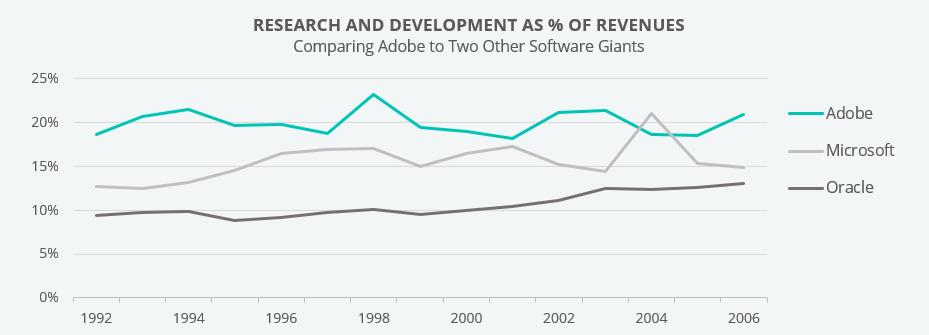

#4: Importance of R&D & Value-Creative M&A

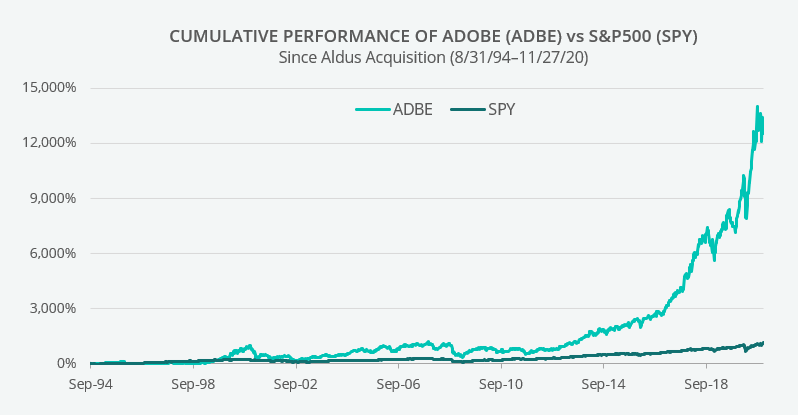

Out of the three companies, Adobe is the one that continued to grow and remain independent. There are many reasons for this. One, major reason, however, is it continued to invest to create a powerful suite of products for its users. By continually improving its core products and by acquiring or creating new products, Adobe assembled a bundle of products with a common user interface and that all worked seamlessly together. Creative professionals could satisfy their needs with just one company that had all the best products: Adobe. The company’s long-term shareholder return speaks for itself on this point.

#5: Customer Lock-In: Standards/Integrations/Plug-Ins

As the desktop publishing industry matured, consolidation followed. Aldus, Adobe, and Quark all added to their core products with complementary products. A good bundle of related, inter-operable products can create lock-in and reduce customer churn.

Two reasons why Quark achieved its dominant position was its focus on the high-end market and the concept of extensions/plug-ins. Third parties could create and sell plug-ins that added new functions to make the lives of Quark users easier. After a publisher makes the heavy, up-front investments in Quark XPress and multiple plug-ins—and this all becomes embedded in their workflows—the odds of switching to a competing product become lower and lower.

#6: Be Weary When a Founder Leaves

Whenever there is a dramatic change at a company, such as when a founder leaves and sells out completely, an investor should always be wary. When the last of Quark’s co-founders sold out to Quark’s CEO, the CEO began to make dramatic changes. Given Quark has always been a privately held company, Andvari can only surmise that changes like outsourcing customer service and software development to India were cost-saving measures meant to fund the purchase of the founder’s shares. Whatever the reason might be, the result over a decade was Quark losing the competitive race with Adobe.

#7: Fertile Grounds of Forced Divestitures

When Adobe acquired Aldus, the FTC would have blocked the deal if Adobe hadn’t agreed to two key provisions regarding professional illustration software. FTC involvement in any proposed deal between companies is a factor Andvari always considers in its investment process. It typically is a high-value indicator that a majority of the market has consolidated down to two or three companies. In turn, this usually means above-average profitability and an increased likelihood of above-average returns to shareholders.

In this case, the FTC found in 1994 that Aldus’s FreeHand and Adobe’s Illustrator were the only two products in the market for professional illustration software. Illustrator had 70% market share and FreeHand had 30%. Having dominant, industry-standard products is a big reason why Adobe has produced exceptional results for shareholders over the years.

Access to the complete, 18-page PDF is available through the Andvari Document Portal. If you would like access to the portal or the full paper, please contact Info@AndvariAssociates.com.

-

_________

--

-

_________

-

IMPORTANT DISCLOSURE AND DISCLAIMERS

Investment strategies managed by Andvari Associates LLC ("Andvari") may have a position in the securities or assets discussed in this article. Andvari may re-evaluate its holdings in such positions and sell or cover certain positions without notice.

This document and the information contained herein are for educational and informational purposes only and do not constitute, and should not be construed as, an offer to sell, or a solicitation of an offer to buy, any securities or related financial instruments. This document contains information and views as of the date indicated and such information and views are subject to change without notice. Andvari has no duty or obligation to update the information contained herein. Past investment performance is not an indication of future results. Full Disclaimer.

© 2020 Andvari Associates LLC